|

| Front and back covers |

The Rabbits by John Marsden and Shaun Tan is one of those picturebooks that leaves you gaping from a mixture of shock and admiration. It was the third picturebook illustrated by Shaun Tan to reach my bookshelf and to be featured on this blog. I've featured The Lost Thing and The red tree.

Both Marsden and Tan are Australians and through this picturebook make a very clear statement about cultural awareness, expertly creating an allegorical tale of colonialism. The Rabbits has been used in secondary schools since it was published in 1998 in areas of the curriculum that include English, Art and Technology, Philosophy, History, Geography and Environmental Studies. But has it been used in ELT? Let's see if I can convince the readers of my blog to consider its possibilities.

I've taken a photo of the front and back covers together - the image is so powerful: a huge ship with a pointed, harpoon-like prow. Napoleon-like creatures stalk around on pin legs, we can't quite make out what they are... though from the title they have to be rabbits. That strip of red on the back cover is actually a collage, a piece of red cloth, fraying at the edges. Could it be from the flags? Or from the invader's coat? The words on this fraying piece read:

"The rabbits came many grandparents ago.

They built houses, made roads, had children.

They cut down trees.

A whole continent of rabbits ..."

|

| The front endpapers |

The endpapers are a calm blue-lilac. Clean water, the home to graceful, long legged birds. What a contrast to the front cover. Is this the land these invaders have arrived at, that they will soon be invading?

|

| The half title page |

The dark brown half title page imitates the format of a well known flag, with pen-inked squiggly writing and some sort of shield in the centre, superimposed over a map. You can peer and peer, but nothing can be discerned or made out.

The title page comes next: a ripped sheet of paper, covering that blue-lilac bird-filled lake. We can see that some of the paper has begun to soak up the water, turning the white into a creeping grey, the birds are moving away from us, their backs are turned and they are all looking to the right, they've seen something we can't see yet. The white paper is both a cover as well as a vehicle for the pond life, as flowers are growing from its edges and dragon flies hum towards the dedications. The title font, as on the front cover, is not quite normal, the 'e' has a strange wave under it and the 't' is uncharacteristic. Are these letters from a past, letters that have changed over time to those we know and recognize today?

|

| Opening 1 |

Opening 1 confirms our haunch, the birds are indeed fleeing, if the book had sound we would hear their calls of alarm, we would hear the snakes hiss in warning. What is that strange black chimney in the horizon? What are the fossil-like shapes in the dark cave behind the snakes? Does Tan want us to think of the time these fossils have taken to form? An age-old land. We read an invisible narrator's words, "The rabbits came many grandparents ago".

|

| Opening 2 |

This illustration is of an immense land, home to tiny creatures, birds and insects. It has been marked by the wheels of a strange machine, which we can just make out on the horizon. Two worlds meet and wonder at each other: "They looked a bit like us ..." they were creatures, they had ears and tails, but they wore clothes and had strange machines... "There weren't many of them. Some were friendly."

And soon more came, and the old people warned us all... "they came by water." And we see the front and back cover as a spread, even more frightening now as we have begun the story, we know the significance of these strange creatures.

We are told and shown how different they are:

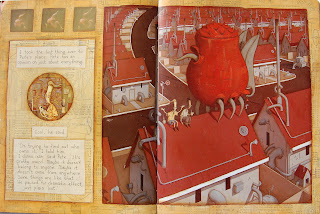

"They didn't live in trees like we did. They made their own houses." This particular spread gives us information in layers. The slightly lighter blue strip at the top is the original layer and belongs to the narrators. They are sitting in their trees, watching their world change. The darker blue is a superimposed layer, the result of the rabbits: we see both the buildings being built and what they will look like. The buildings are like puzzles, already spewing black smoke. Everything is mechanical, even the rabbits seem so, the symmetry emphasizing the mechanical way they changed the world.

Not only were the rabbits' homes different, but "...they brought new food, and they brought other animals." The illustrations show us massive grass eating sheep, machines dressed in lambs' wool. Cows, already marked for the butcher's knife. The land is covered in these strange creatures, either in the fields or pilled high on spindly locomotives. More words tell us that "... some of the animals scared us." But that's not all, "... some of the food made us sick" (the last three words turned upside down, as though rolling over with belly ache). The illustration shows a rabbit giving a bottle to the aboriginal creature collaged upon another illustration of a dried up water bed, littered with flapping, gasping fish.

There was no stopping the rabbits, they spread across the country. There was fighting, "but there were too many rabbits"

"We lost the fights." Those fossils we saw at the beginning, denoting an ancient world, dominated above by the rabbits' flags, the aboriginals, prisoners in their age old world, defeated below.

The atrocities continue: "They ate our grass. They chopped down our trees and scared away our friends... "

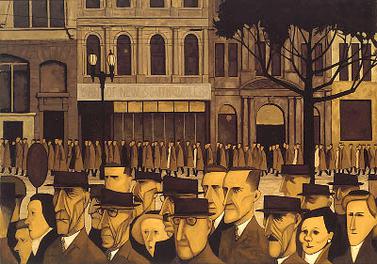

I find this spread the most shocking: hundreds of kites, with baby animals inside, being pulled by strange air machines. Mother creatures, as though dancing, hands raised towards their children, you can almost hear them moaning. And the rabbits, big and black, their vertical backs turned against the mothers. They have red and yellow eyes and the peacock feather pens mirror these evil eyes, dripping with the blood red ink they have just used to write on the certificates. These contain the verbal text of this page, each word on a separate sheet of paper, as though being spoken in jerks of distress, "and . stole . our . children."

"... everywhere we look there are rabbits." The statue in recto, a large rabbit, the motto MIGHT = RIGHT. A grey automated world, polluted and literally filled with rabbits, right to the very edges of the page. Can you see the only aboriginal creatures on the steps of the statue? The fallen kite? The rabbits holding masks? The gigantic curved chimneys, sucking in the blue sky and puffy clouds? A curious image, a frightening image.

"The land is bare and brown and the wind blows empty across the plains. Where is the rich dark earth brown and moist? Where is the smell of rain dripping from the trees? Where are the lakes, alive with long legged birds?"

A final verso page shows a small cameo illustration against a black background. Two solitary creatures, a rabbit and an aboriginal.

"Who will save us from the rabbits?". The land is wasted, littered with bones, lost and broken pieces of machinery and empty bottles. A small water hole reflects the stars in the sky. Can we read this as an image of hope? Is there any hope left? If we turn again to the back endpapers, we return to the bird-filled lake of cool lilac-blue water. A distant memory? A possible future?

When I first saw this picturebook I got goose bumps, and every time I look at it I get that goose bumpy feeling. It's quite something. A simple verbal text alongside such complex visual images, makes for much interpretation. There are many issues here and therefore lots of opportunities for talk and discussion. If you are teaching English through history, could this picturebook be of use? If your programme includes such topics as multiculturalism, could it be of use? Or, if you happen to have a group of interested teenagers, keen to talk and discuss, keen to put the world to rights, could this book be of use? I'd say 'yes' on all three occasions.

We are told and shown how different they are:

|

| Opening 5 |

|

| Opening 6 |

There was no stopping the rabbits, they spread across the country. There was fighting, "but there were too many rabbits"

|

| Opening 8 |

The atrocities continue: "They ate our grass. They chopped down our trees and scared away our friends... "

|

| Opening 10 |

|

| Opening 11 |

"The land is bare and brown and the wind blows empty across the plains. Where is the rich dark earth brown and moist? Where is the smell of rain dripping from the trees? Where are the lakes, alive with long legged birds?"

A final verso page shows a small cameo illustration against a black background. Two solitary creatures, a rabbit and an aboriginal.

|

| Back verso |

When I first saw this picturebook I got goose bumps, and every time I look at it I get that goose bumpy feeling. It's quite something. A simple verbal text alongside such complex visual images, makes for much interpretation. There are many issues here and therefore lots of opportunities for talk and discussion. If you are teaching English through history, could this picturebook be of use? If your programme includes such topics as multiculturalism, could it be of use? Or, if you happen to have a group of interested teenagers, keen to talk and discuss, keen to put the world to rights, could this book be of use? I'd say 'yes' on all three occasions.